Need Help Finding the right wine?

Your personal wine consultant will assist you with buying, managing your collection, investing in wine, entertaining and more.

NYC, Long Island and The Hamptons Receive Free Delivery on Orders $300+

Checkout using your account

Checkout as a new customer

Creating an account has many benefits:

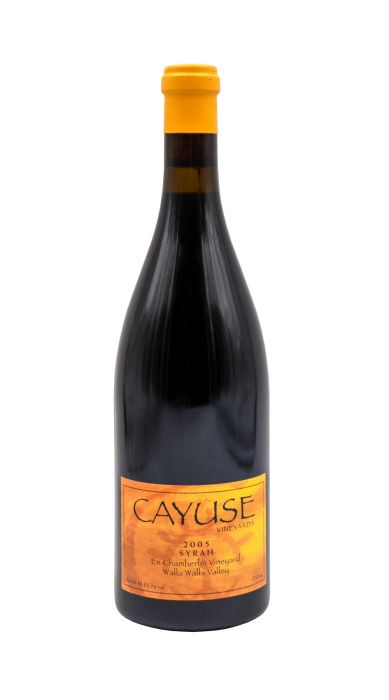

2005 Cayuse Syrah en Chamberlin Vineyard

94 RP

Robert Parker | 94 RP

| Type of Wine | Washington Red |

|---|---|

| Varietal |

Shiraz/Syrah

: Something magical occurred when two ancient French grapes procreated and the varietal of Syrah entered the world of winegrowing. The exact time period of its inception is still undetermined; however, the origin of Syrah’s parentage confirms it was birthed in the Rhone Valley. DNA testing performed by UC Davis has indicated that Syrah is the progeny of the varietals Dureza and Mondeuse Blanche, both of Rhone origin. Syrah dominates its native homeland of Northern Rhone and has become one of the most popular grape varietals in the world. Syrah, Shiraz and Petite Sirah have often been confused and misunderstood, some consumers believing them to all be the same grape, while others thinking the opposite. Petite Sirah is actually the offspring of Syrah and Peloursin and though related, is an entirely different grape variety. Its official name is Durif, for the name of the French nurseryman who first propagated the varietal in the 1880s; it is called Petite Sirah in California (due to the resemblance of Syrah, but smaller berries). Syrah and Shiraz are the same grape. Producers in Australia have been labelling Syrah as “Shiraz” since James Busby first introduced the varietal to the continent. The Scottish viticulturist brought Syrah from France to Australia in the middle of the 18th century and labelled the cuttings as “Sycras” and “Ciras,” which may have led to the naming. Most California vintners label their bottlings as Syrah and of course in French style and tradition, the name of the village or area the grape is cultivated dictates the label name. The Syrah grape is at home in Northern Rhone where the climate is cool and the terroir is filled with gravel, schist, limestone, iron, granite and sandy soils. It thrives on rocky, hilly terrain with a southern exposure, due to its need for sunlight. Syrah is a very vigorous grape with a spreading growth habit. The berries are small to medium oval shaped blue-black and tend to shrivel when ripe. Today, Syrah is one of the most popular and widely planted grape varietals in the world, covering almost 190,000 hectares across the earth’s surface. It is the only red grape variety permitted by AOC regulations in the appellations of Hermitage and Cote-Rotie, where it has breathed life into some of the most tremendous wines on the planet. Languedoc-Roussilon has the most surface area planted in France with 43,200 hectares dedicated to Syrah. The varietal is used for blending in Southern Rhone, Provence and even Bordeaux. Syrah has spread worldwide from Australia to California and South Africa to Spain creating the ‘New World’ hype of the varietal. Since the 1990’s, Syrah winegrowing and production has increased exponentially; for example, in 1958 there were a mere 2,000 hectares planted in France. By 2005 that number increased to over 68,000 hectares and today it is well over 70,000. The same holds true for California, Australia and other ‘New World’ producers that have jumped “all in.” World-wide there are approximately 190,000 hectares of Syrah currently being cultivated. The allure of Syrah has taken the world by storm, but is important to note where the hype began. Long before Syrah was being stamped with ‘New World’ or of ‘cult status,’ the tremendous quality of Hermitage was being written about in Thomas Jefferson’s diary. Today, the grape variety can be grown, fashioned, named and enjoyed in a myriad of ways, but the quality of Syrah grape remains the same – incredible. |

| Country |

US

: As one of the most prolific and innovative wine regions in the world, America is a joy to explore. Most wine connoisseurs will agree that the nation's finest and most compelling wines are being produced today, which means that we have front-row seats to one of the most inspirational stories in wine history. While other regions tend to focus on specific wine styles and have somewhat strict rules as to which varietals you could grow, areas like California have few such restrictions in place. As a result, creative visionaries behind America's most reputable estates have been able to develop compelling, unique, and innovative styles, with a level of terroir expression that rivals even France's largest giants. |

| Region |

Washington

: While California definitely owns the spotlight when it comes to excellent American wines, Washington winemakers should certainly not be underestimated. While their traditional focus was set firmly on refreshing, illustrious white wines, they've adopted French red varietals like Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Since then, they've been achieving excellence in both categories and can compete with the world's most prestigious viticultural titans. Flavor-wise, you can expect a healthy amount of variety when it comes to Washington's finest wines. From acidic and fruity bottles that can shake you up from even the deepest slumber or sadness to rich and ripe powerhouses that command the respect of everyone in the room after as much as a single whiff. Juicy raspberries that gently tickle your tongue, deep and noble blackberries, intense cherries and earthen oak - these are the flavors that characterize this region, despite the presence of an entire orchestral symphony of other aromatic notes. A sampling of fine wine from Washington is a lot like being seduced, so why not uncork one of these bottles for a potential or existing partner? With a drink of this quality, those romantic sparks will turn into a fireworks display, as your emotions are laid bare and intensified, and you make a connection that can last a lifetime. |

Need Help Finding the right wine?

Your personal wine consultant will assist you with buying, managing your collection, investing in wine, entertaining and more.